03-05-2016

Nutritional Treatment for Dermatological Conditions

Ageing of the skin

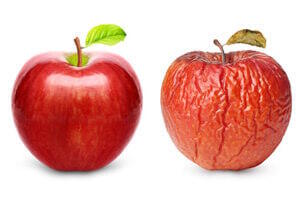

The ageing process produces gradual changes to the skin: drying, wrinkles, slackness, irregular pigmentation and a variety of proliferative damage. From the age of around 50, skin ageing starts to be clearly visible. The skin becomes drier, rougher and thinner. This latter effect means the skin creases more easily and veins becomes more apparent. In some people, the skin takes on a thickened appearance in which case deep furrows appear to varying degrees.A number of factors, such as heredity, the weather, hormones, smoking and nutrition affect how the skin ages, but one of the most significant accelerators of skin ageing is the sun. Ultraviolet rays damage the epidermis and dermis. Frequent and prolonged exposure to the sun can thus cause problems such as lentigo (liver spots). Those parts of the skin most exposed to the sun, such as the face, neck – especially the nape – and hands, age faster. In serious cases, UVA exposure can lead to the development of cancerous tumours. We are all born with our own level of ‘sun resistance’, but once we go beyond it, we start to develop signs of skin ageing, solar keratosis and potentially skin cancer. The sun’s effects are dose-dependent and accumulate with age. Fine lines and wrinkles – which are largely sun-induced - are inevitable but we can slow down their arrival by exercising caution over UV exposure and by using moisturiser every day.

DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) is a hormone produced by the adrenal (or suprarenal) glands (located behind the kidneys) and is the precursor of male and female sex hormones. The DHEAGE study, which monitored 280 healthy men and women aged 60-79, confirmed that blood levels of DHEA sulphate fall as we get older; indeed they start to decline from around the age of 25. One group of subjects was given 50mg/day of DHEA for a year, and the other a placebo. Follow-up occurred at three, six and twelve months. DHEA’s efficacy was particularly notable in women, especially those aged over 70. It improved skin hydration and production of sebum (an oily secretion which forms a protective film maintaining the skin’s suppleness and defending it against microbial and environmental attack). DHEA was also associated with less age-related skin pigmentation, especially on the face, and less pronounced thinning of the skin.

The skin is essentially made up of three layers, each comprising different types of cells:

The epidermis:This consists predominantly of keratinocytes (constituting 80-90% of all epidermal cells) which produce the stratum corneum (the human body’s principal barrier), melanocytes (melanin-forming cells) and Langerhans cells (antigen-presenting cells).

The dermis:This contains fibroblasts, endothelial cells in the capillaries, mastocytes and histiocytes, in a matrix of protein fibres.

A subcutaneous fat layer:This is made up of adipocytes (fat cells) and acts as a ‘shock absorber’ ensuring protection and isolation from adjacent structures.

The role of nutrients in dermatology

Some nutrients – vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids and amino acids - play a major role in skin protection. For example, deficiency in B group vitamins (B2, B3, B5, B6, B8, B9, B12) often produces mucocutaneous symptoms: dermatitis, cheilitis (inflammation of the lips), perlèche (cracks at the corner of the mouth), alopecia (temporary hair loss), and depigmentation.Vitamins and antioxidants

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) plays a part in protecting the skin. Deficiency manifests as mucocutaneous and ocular symptoms. Skin damage can take the form of seborrhoeic dermatitis on the face, primarily on the nasal wings and sometimes on the ear lobes or ends of eyebrows. Hyperpigmentation sometimes occurs on the vulva and scrotum.

Vitamin B3 (niacin) also helps maintain healthy skin. A lack of B3 can cause pellagra, the most typical symptoms of which are skin-related. Symmetrical erythema (skin reddening) appears on exposed parts of the body - the head, neck and extremities – which are painful, producing a burning sensation. Lesions are above all oedematous because they peel, leaving the skin dry, brownish, rough and atrophic. Pellagra is also associated with digestive, mental and haematological symptoms.

Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) also contributes to the healing process and promotes activity of tissues, mucosa, hair and skin. A lack of B5 manifests in the skin as alopecia and ulcers. Deficiency in vitamin B5 and B8 can together produce alopecia or seborrhoea of the scalp. Combined use of these B vitamins is used to treat alopecia (1) and helps control seborrhoea, stem hair loss and stimulate regrowth (2).

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) acts as an anti-stress agent - stress having been identified as an aggravating factor in acne (anxiety, premenstrual period). Amongst others, a lack of B6 can cause various skin disorders: seborrhoeic dermatitis, perioral dermatitis, cheilitis and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue). Lack of vitamin B6 results in considerably less cysteine being absorbed into the skin and the teratogenic ?? area of the hair.

Vitamin B8 (biotin) reduces skin secretions, thus preventing oily skin. Deficiency gives rise to mucocutaneous problems such as perioral dermatitis, rashes, intertrigo, onyxis (ingrowing nails) and candidiasis as well as neurological and other symptoms. It promotes skin renewal by acting on the germinative layer of the dermis and epidermis. It is easily absorbed by the hair - of which it is a natural component - particularly by dry, damaged hair, and it stimulates growth of the hair follicle. In male-pattern baldness, vitamin B8 supplementation enables hair loss to be temporarily halted and improves dull, brittle and depigmented hair. It is also used to treat seborrhoeic dermatitis in breast-fed babies (‘cradle cap’, nappy rash, and Leiner-Moussous desquamative erythroderma). It has proven follicle-stimulating and anti-seborrhoeic effects.

Vitamin A (retinol) protects the superficial layers of the skin by preventing the spread of bacteria, and improves healing. The first signs of vitamin A deficiency are nyctalopia (defective vision in dim light), skin dryness and hyperkeratosis (abnormal skin thickening) on the outer side of the lower limbs.

Beta-carotene is a carotenoid. It protects our skin from the sun, and like vitamins C and E, has an antioxidant role. Beta-carotene can be converted into vitamin A. It plays a role in cell communication and differentiation, as well as in the growth and integrity of skin cells. Deficiency manifests as dryness of the skin with atrophy of the sebaceous and sweat glands, and a thickening of the stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis), giving the skin a rough appearance. It also has a photo-protective effect (against UV rays).

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) has antioxidant and skin-protective effects. Lack of vitamin C can result in scurvy in adults and Barlow’s disease in children. Mucocutaneous symptoms include oedema of the extremities, hypertrophic gingivitis with bleeding gums and potential tooth loss, follicular hyperkeratosis and cutaneous haemorrhages (petechiae – small red or purple spots or ecchymoses - bruises). Insufficient vitamin C intake also causes problems with healing. Vitamin E (tocopherol or tocotrienol) is also an antioxidant and thus prevents oxidation of essential fatty acids. It protects cell membranes, and in conjunction with beta-carotene and vitamin C, helps slow down ageing of the skin.

Essential fatty acids

Omega-3 essential fatty acids in fish oils (EPA, DHA) and certain omega-6 fatty acids (g-linolenic acid or GLA) in borage and evening primrose oils ensure the skin remains supple, radiant and hydrated.

Amino acids

Protein hydrolysates are beneficial for hair growth. A lack of absorbable protein in the diet will slow down hair growth and may even cause hair loss. Cysteine is a sulphur-containing amino acid which is abundant in the skin. Taurine acts in an antioxidant capacity, helps eliminate bile salts and works in synergy with magnesium and vitamin B6.

Minerals and trace elements

Magnesium helps activate the B group vitamins. Essential to cell membrane integrity, it also combats stress, thus helping reduce one of the factors known to aggravate acne.

Zinc contributes to skin healing by inhibiting the inflammatory response. Extensive burns tend to heal poorly and become infected unless zinc supplements are taken (3). A lack of zinc is responsible for perioral dermatitis (acrodermatitis enteropathica).

Silicon is essential for production of collagen and elastin fibres in connective tissue - depletion of silicon impairs the tissue’s integrity and elasticity. Organic silicon compounds called silanols are thus recommended for improving wrinkles and stretchmarks as well as skin elasticity. From around the age of 40, a lack of organic silicon causes the skin to develop wrinkles and become significantly drier.

Eczema

There are different forms of eczema:1. Contact eczema:this appears in various circumstances – either as a result of direct contact (handling of chemicals, exposure of the hands to allergens …), or airborne contact (allergens in the atmosphere which come into contact with the body’s integumentary system), or through foreign bodies accidentally injected into the skin.

2. Atopic eczema:this is a common form, especially in children. In Europe, it affects between 12% and 15% of infants under 2, and 2%-5% of children under 5. Eczema can develop at any age but most often appears between the second and fourth month of life. Characterised by flare-ups, it is a chronic condition which can be very debilitating, and is directly linked to asthma and hay fever. It manifests as dry skin, and red, itchy, thick patches of eczema.

There are two concepts involved in the development of eczema:

1. The atopic nature of the condition which is a major factor. In 70%-80% of cases, there is a family history and increased presence of E immunoglobulins.

2. The environment, with multiple allergens (dust mites, food allergies…) triggering a specific inflammatory response which releases histamine and numerous mediators in damaged skin, resulting in patches of eczema.

Examination of the plasma phospholipids of a group of 50 young adults with atopic eczema showed increased linoleic acid with a lack of g-linolenic acid (GLA) and its metabolites, such as dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA)) and arachidonic acid. This suggests that atopic subjects are functionally deficient in delta-6-desaturase which converts linoleic acid into GLA.

Atopic individuals can be extremely sensitive to the side-effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories; topical application of nicotinic acid (vitamin B3) can cause a flushing sensation. Such reactions can be explained by a lack of precursors of prostaglandins (4).

Evening primrose and borage oils

It would seem logical, therefore, for atopic individuals to supplement with the GLA that they are unable to produce themselves. There are two vegetable oils rich in GLA: evening primrose oil (Œnothera biennis) which contains 8%-10%, and borage oil (Borago officinalis) which contains at least 23%. A study compared the effects of evening primrose oil (71% linoleic acid, 7-10% GLA), safflower oil (Carthamus tinctorius) (75-78% linoleic acid, no GLA) and paraffin oil (5). The evening primrose oil produced an increase in DGLA levels without raising those of arachidonic acid, while the safflower oil raised levels of linoleic and arachidonic acids but not those of DGLA. Supplementation with evening primrose oil increased the amount of DGLA in white cell phospholipids by 45%, phosphatidylcholine by 46% and phophatidylethanolamine by 14% in healthy skin. The g-linolenic acid present in evening primrose and borage oils is well assimilated by the body and supplementation compensates for the decreased GLA production responsible for atopy.A meta-analysis published in 1989 (6) looked at nine controlled studies (5 crossover, 4 placebo-controlled), evaluating the effect of evening primrose oil as a treatment for atopic eczema. The overall analysis showed that severity scores improve significantly as a result of evening primrose oil supplementation, from both patient and doctor perspective. The effect on itching is particularly notable. Clinical improvement correlates positively with the level of DGLA concentration. The findings of this meta-analysis have been corroborated by newer studies - evening primrose oil’s efficacy has been confirmed in atopic children, with an attendant rise in DGLA levels in red blood cell membranes (7). 2-4g/day is of evening primrose oil is the preferred dose though it may take up to six months before benefits are felt.

In a randomised, placebo-controlled study of 106 eczema sufferers treated with a topical steroid, taking 500mg of borage oil led to increased levels of GLA metabolites, and in a sub-group of patients, there was also a rise in DGLA levels in red blood cells following borage oil supplementation (8).

Fish oil concentrated in EPA and DHA

In a double-blind study, patients with atopic eczema were given either 3g of EPA + DHA or olive oil for 12 weeks. In the EPA/DHA group there were improvements in severity scores, itching and subjective symptoms, compared with those taking olive oil (9). In other research (10), four months’ supplementation with 6g of fish oil concentrated in omega-3 versus peanut oil, produced a 30% decrease in symptoms compared with a 24% decrease for subjects taking peanut oil, in correlation with an increase in levels of omega-3 in serum phospholipids.In a study of 21 dogs with atopic eczema, administration for eight weeks of a combination of borage oil (either 176mg/kg or 88mg/kg) and fish oil was found to reduce redness and excoriation (scratch marks) while administration of olive oil (204mg/kg) provided no such improvement (11). Combining fish oil and evening primrose oil may be more effective than either given in isolation.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a form of chronic dermatitis characterised by flare-ups of erythematosquamous plaques which are sharply-delineated, roughly bi-lateral and symmetrical. There are several types of psoriasis which exhibit different characteristics:Psoriasis vulgaris:

1. A widespread skin rash, roughly symmetrical, often itchy.

2. Specifically affects the elbows, knees, shins, trunk, scalp and nails.

Topographical forms:

1. Psoriasis of the scalp: produces either large plaques extending to the forehead, or defined patches without alopecia.

2. Psoriasis of the nails: may have a specific appearance where the nail plate is covered in thimble pitting, or non-specific with vertical ridges and horizontal grooves.

3. Palmo-plantar psoriasis (psoriasis of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet) which either takes the form of erythematous scaly plaques (with rounded polycyclic contours) and calluses (ring-shaped with a hard nucleus), or has the appearance of localised pustular psoriasis and inverse psoriasis (bright red plaques, non- or almost non-scaly, smooth and shiny or oozing patches covered with a whiteish coating).

4. Psoriasis of the mucous membranes: rare.

May be accompanied by joint pain, especially in the hands, feet and lower back.

In France, psoriasis currently affects 2 million people, with almost 60,000 new cases diagnosed each year. Incidence is influenced by geographical and environmental factors. Both men and women are affected. Though it can start at any age, it is most common between the ages of either 20 and 30, or 50 and 60. There is a genetic predisposition. Children whose parents have psoriasis are at greater risk of developing it too – 8% if one parent is a sufferer, and 40% if both have the condition – or an identical twin.

The epidermis renews itself too quickly so that dead cells cannot be eliminated and accumulate instead.

Dietary factors

The effect of dietary advice on the severity of chronic psoriasis plaques was examined in 18 patients. They were asked to eat 170g/day of white fish for four weeks. The patients were then divided into two groups: one continued the white fish regime while the other group replaced it with 170g of oily fish for six weeks. At the end of this second period, the regimes were swapped for a further six weeks. Consumption of the oily – but not the white – fish produced a modest clinical improvement (of 11%-15%), together with an increase in plasma EPA concentrations. Daily consumption of oily fish (mackerel, sardines, salmon, pilchards and herrings) is particularly beneficial in the treatment of psoriasis (12).An Italian study looked at the diets of 682 subjects aged 16-65 - 316 psoriasis patients and 366 controls. Psoriasis appeared to be positively associated with BMI (weight/height). Inverse relations were observed for consumption of carrots, tomatoes and fresh fruit as well as the index of beta-carotene intake (13).

Fish oil concentrated in EPA and DHA

The effect of an n-3 fatty acid supplement on psoriasis and atopic eczema was examined in a four-month study in which 41 patients received 6g/day of oil highly concentrated in EPA and DHA, or 6g/day of corn oil. DHA and EPA assimilation in serum phospholipids was significantly greater in the psoriasis patients (EPA + 480%, DHA + 40%) than in those with atopic eczema (EPA + 200%, DHA + 14%). This effect was accompanied by a decrease in interleukin 2 receptor alpha (CD25), a pro-inflammatory cytokine receptor (14). Oxidative stress markers were greater in psoriasis patients: levels of arachidonic acid (an omega-6 precursor of inflammatory metabolites) and plasma malondialdehyde (MDA - a product of lipid peroxidation), and activity of platelet and erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase (antioxidant effect) were all higher while selenium levels were lower. High levels of arachidonic acid incite production of leukotriene B4 - a pro-inflammatory metabolite. Two months’ supplementation with omega 3-rich fish oil enabled the arachidonic acid in cell membranes to be replaced by EPA and DHA. It led to a reduction in MDA and improved stimulation of glutathione-peroxidase (15, 16). EPA is the precursor of leukotriene B5 which unlike B4, has no pro-inflammatory effect. Administration of 1.8g/day of EPA and 1.2g/day of DHA to 30 psoriasis patients increased the LTB5/LTB4 ratio from 0 to 0.42 which reduced inflammation (17). EPA and DHA supplementation thus helps normalise membrane composition of polyunsaturated fatty acids.An initial 10-day study (18) of 30 patients investigated the effects of intravenous administration of lipid emulsions rich in either omega-3 (2.1g/day of EPA and 2.1g/day of DHA) or omega-6. Disease severity decreased in all those receiving omega-3. This effect was linked to increased formation of EPA derivatives such as leukotrienes B5 and A5 (in white cells). Platelet activation factor (PAF) decreased in the omega-3 group, but increased in the omega-6 group. A similar 14-day study (19) of 83 hospitalised patients with chronic and severe psoriasis plaques subsequently confirmed the efficacy of supplemental omega-3s. It was shown to be more effective than omega-6 in terms of erythema, scaling, infiltration, severity per body area, and patient and doctor assessment criteria. Omega-3 intake (though not omega-6) improved free concentration of EPA in plasma and that of B5 leukotrienes in neutrophils. EPA supplementation thus offers an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing platelet hyperactivity and by raising levels of B5 leukotrienes.

A study (20) monitored 28 people with chronic psoriasis, half of whom were given supplemental EPA (1.8g/day) and DHA (1.2g/day), and half a placebo. After eight weeks, the supplemented group reported decreases in itching, redness and severity, though lesion size remained the same. When omega-6 are combined with omega-3, the latter’s anti-inflammatory effect on psoriasis disappears (21).

For faster efficacy, fish oil can be combined with a medically-prescribed, low-dose, vitamin A-derived retinoid. This combination is more effective than a retinoid used on its own (22). Psoriasis patients have higher levels of plasma triglycerides compared with controls. This is exacerbated by taking vitamin A derivatives (etretinate) but taking EPA (1.8g/day) and DHA (1.2g/day) at the same time reduces the increase in triglycerides by 70% and that in cholesterol by 45% (23). A four-week pilot study of 25 psoriasis patients treated with a retinoid (etretinate) showed that supplementing with 3g of EPA and DHA produced a 27% decrease in triglycerides and an increase in HDL cholesterol (24).

Vitamin A and beta-carotene

A Turkish study showed a decrease in glutathione levels and much lower glutathione peroxidase activity in plasma and red cells in people with psoriasis compared with healthy individuals, whereas levels of beta-carotene and malonedialdehyde (MDA) in plasma were higher. These results suggest that lipid peroxidation and decreased antioxidants may play a role in psoriasis (25).In a study in which the vitamin A (retinol) status of 107 psoriasis patients and 37 healthy volunteers was investigated (26), serum retinol levels were found to be lower in 28 patients with extensive plaque lesions or pustular psoriasis than in controls. Concentrations of retinol and derivatives were measured from specimens taken from both healthy and affected skin of psoriasis patients. Retinol concentrations were found to be largely similar to those of healthy controls but carotenoid levels were 25%-50% lower in both skin samples. Supplementation with beta-carotene and canthaxanthin increased the carotenoid levels in healthy skin samples by 160% and by 610% in affected skin, without altering vitamin A content. Other studies have confirmed the low vitamin A status of psoriasis patients.

Vitamin D

There are two forms of vitamin D: ergocalciferol present in plants and cholecalciferol present in animal products and produced by our bodies. Although vitamin D is classed as a fat-soluble vitamin, it actually functions as a hormone. Our skin contains the vitamin D precursor 7-dehydrocholesterol which is converted into cholecalciferol in the skin on exposure to the sun’s rays. Two steps are then required for it to become active: the first takes place in the liver, is dependent on the hormone parathyroid and results in the formation of calcidiol. The second occurs in the kidneys and results in calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, which has been shown to be effective in treating psoriasis. Calcipotriol, a vitamin D derivative, is effective when applied locally as a short- or long-term treatment for moderately severe psoriasis plaques. Lesions are whitened or improved in 60-70% of patients after monotherapy with a calcipotriol cream. Concomitant use of UVB phototherapy increases the anti-psoriasis effect. Overall, this vitamin D derivative represents a better alternative to topical steroids for treating localised psoriasis. Up to 25 µg/day (1000 IU/day) can be taken in complete safety (27). Higher doses should only be taken under medical supervision.Oregon Grape (Mahonia aquifolium)

Some studies suggest that Oregon grape may help reduce symptoms of psoriasis (28, 29, 30). In an open study of 443 psoriasis patients, supplementing with Oregon grape for 12 weeks was shown to benefit 73.7% of individuals (31). A double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 82 psoriasis sufferers assessed the grape’s efficacy and found it produced good results based on participant assessment.Thermal treatments

Thermal treatments are often helpful. The Dead Sea, in particular, situated 400m below sea level, offers therapeutic benefits. 80% of those affected by psoriasis and other diseases of the skin or joints see improvements in their condition. Four weeks’ treatment gives around 10 months’ remission from skin diseases, without the need to take medication. Treatment consists of sun- and sea-bathing, with duration and frequency calculated according to skin type, season, time of exposure and the disease.Acne

Acne is a disease of the pilosebaceous follicles involving sebaceous hypersecretion, follicular hyperkeratinisation and bacterial proliferation. Acne primarily affects the face, though it may also appear on the neckline, shoulders and back. Juvenile acne is the most common skin disorder, with 80% of adolescents suffering from it at some point – 85% of them mildly, but 15% seriously. Other forms include baby acne – which mostly affects the face, adult acne (which develops after the age of 30) and often requires hormone investigation in women, and iatrogenic acne, due to certain drugs or oily cosmetic creams. Children and old people suffer less frequently from acne because of their different hormone patterns.Hygiene habits and the use of certain cosmetics may explain why topical anti-acne preparations are poorly-tolerated or why retentional acne persists. Certain drugs can encourage flare-ups – often it is the progestins with androgenic activity that are to blame, and sometimes long-term use of vitamin B12. Less frequently, acne may be stimulated by corticosteroids, halogens (bromine, iodine), lithium, anticonvulsants or androgens.

How does acne develop?

The process is well-known. The pores become blocked. Bacterial flora is an important element in the development of acne. Anaerobic bacteria (that exist without oxygen) proliferate and if they do so to a sufficient degree, there will be a rupture below the epidermis, allowing infection to spread under the skin. The essential factor in predisposition to acne may be the thickness of the skin - the thinner the skin, the less likely it is that the pores will become blocked. Various irritants (the sun, chlorine, cold, perspiration, etc), as well as excessive cleansing, may contribute to thickening of the epidermis while products such as salicylic acid may help reduce epidermal thickness. Exposure to the sun increases sebum production and leads to thickening of the skin. The temporary improvement that some acne sufferers experience after being in the sun is probably due to a change in skin tone but the effects are damaging in the long-term. Dihydrotestosterone, derived from testosterone, may play a role. Some people may be predisposed to producing this derivative which may affect sebum production.

Zinc

A number of double-blind studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of zinc in treating acne. Zinc reduces inflammation in a number of ways - by inhibiting production of the sebaceous glands through its effect on 5 a-reductase, by reducing zinc content in white cells, which is responsible for reducing their chemotaxis (movement towards their target) and by inhibiting production of nitric oxide induced by inflammatory cytokines on keratinocytes (34). In the 1970s and 80s, zinc was given at high doses in sulphate form and sometimes caused digestive problems. Nowadays, moderate doses in gluconate or citrate form are suggested. Administration of zinc for three months helped reduce the number of pustules, papules, infiltrates and cysts (35). In 1989, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study was published demonstrating the efficacy of 30mg/day zinc gluconate on pustular and inflammatory forms of acne (36). The efficacy of this dose was confirmed by a recent trial of 67 subjects which compared three months’ regular administration with a protocol that included a loading dose over three weeks. The overall amount of zinc administered was similar (37). In practice, zinc should be used alongside antibiotics, or on its own, particularly in situations where antibiotics are contraindicated (pregnancy, exposure to the sun in the case of tetracyclines).

Selenium

Individuals affected by acne vulgaris have low levels of selenium (38). Male acne patients were shown to have low glutathione peroxidase activity compared with controls; however, women with acne and controls who were both taking the contraceptive pill had similarly high levels of glutathione peroxidase activity, higher than either group not taking the pill. Research involving 47 women and 42 men in which they took selenium supplements at a dose of 400 µg/day, and vitamin E at a dose of 20mg/day for 6-12 weeks showed that the treatment helped reduce pustules and slightly increase glutathione peroxidase activity. Previous values returned once treatment was stopped (39).

Skin appearance and nutrition

The skin reflects the state of our health and our lifestyle. Some substances are damaging to skin health and affect its appearance, with consequences of varying severity (yellowish tinge, skin cancer).Among them is tobacco: it reduces the flow of blood and oxygen to the skin with a number of visible consequences: the skin becomes duller and less supple, and wrinkles develop prematurely and are more pronounced. The effects are particularly apparent because smoking reduces the benefits of facial skincare.

There is a direct relationship between dry skin and inadequate intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Playing a key role in the skin’s barrier function, unsaturated fatty acids contribute to healthy skin hydration. Those with dry skin will benefit from consuming borage and evening primrose oils, and fish oils. Likewise, they should eat oily fish such as salmon, tuna, sardines and mackerel (40). De même, il faut consommer des poissons gras de type saumon, thon, sardine, maquereau.

Conclusion

Nutrition and nutritional supplements can have a significant impact on some skin diseases (psoriasis, atopic eczema and acne). First and foremost, a healthy, varied diet, rich in antioxidants and omega-3s, together with good hydration (drinking at least 1.5l of water a day) are essential. Nutritional supplements can be used either on their own or as an adjunct to conventional drug treatments. Atopic eczema is linked to deficient 6-desaturase activity which causes insufficient production of g-linolenic acid; evening primrose and borage oils help eliminate atopic symptoms by restoring those GLA levels. Consuming fish oils concentrated in EPA can counteract the excess of inflammatory metabolites produced in psoriasis and help achieve a cure. Regular consumption of oily fish is another important step. Since acne has a strong inflammatory component, zinc should be taken by sufferers to inhibit inflammation and reduce its associated symptoms. Last but not least, antioxidant intake is particularly important for the skin, especially vitamin E, beta-carotene and selenium as a constituent of glutathione peroxidase. And it must be remembered that any supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids should be accompanied by concomitant supplementation with fat-soluble antioxidants, particularly vitamin E. A sensible dose is 200-400mg of alpha-tocopherol-equivalent per gram of EPA+DHA.BIBLIOGRAPHY

1 Cheirif-Cheikh J.L., Hincky M. Recrudescence de l'alopécie. Concours Médical. 1977, 99(27), 4461-4464.

2 Fabre PH. Les alopécies, leurs traitements par vitaminothérapie : vitamine B5 et biotine. Tempo Médical. 1987, n°274.

3 Delaporte E,Gaveau D, Piette F, Bergoend H. Indications et modalités du traitement par le zinc en dermatologie, Sem Hôp Paris, 1989, 65, n°43-44, 2657-2660.

4 Manku MS, Horrobin DF, Morse N, Kyte V, Jenkins K, Wright S, Burton JL. Reduced levels of prostaglandin precursors in the blood of atopic patients: defective delta-6-desaturase function as a biochemical basis for atopy. Prostaglandins Leukot Med 1982 Dec;9(6):615-28

5 Horrobin DF, Ells KM, Morse-Fisher N, Manku MS. The effects of evening primrose oil, safflower oil and paraffin on plasma fatty acid levels in humans: choice of an appropriate placebo for clinical studies on primrose oil. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1991 Apr;42(4):245-9

6 Morse PF, Horrobin DF, Manku MS, Stewart JC, Allen R, Littlewood S, Wright S, Burton J, Gould DJ, Holt PJ, et al. Meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies of the efficacy of Epogam in the treatment of atopic eczema. Relationship between plasma essential fatty acid changes and clinical response. Br J Dermatol 1989 Jul;121(1):75-90

7 Biagi PL, Bordoni A, Hrelia S, Celadon M, Ricci GP, Cannella V, Patrizi A, Specchia F, Masi M. The effect of gamma-linolenic acid on clinical status, red cell fatty acid composition and membrane microviscosity in infants with atopic dermatitis. Drugs Exp Clin Res 1994;20(2):77-84

8 Henz BM, Jablonska S, van de Kerkhof PC, Stingl G, Blaszczyk M, Vandervalk PG, Veenhuizen R, Muggli R, Raederstorff D. Double-blind, multicentre analysis of the efficacy of borage oil in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol 1999 Apr;140(4):685-8

9 Bjorneboe A, Soyland E, Bjorneboe GE, Rajka G, Drevon CA. Effect of n-3 fatty acid supplement to patients with atopic dermatitis. J Intern Med Suppl 1989;225(731):233-6.

10 Soyland E, Funk J, Rajka G, Sandberg M, Thune P, Rustad L, Helland S, Middelfart K, Odu S, Falk ES, et al. Dietary supplementation with very long-chain n-3 fatty acids in patients with atopic dermatitis. A double-blind, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol 1994 Jun;130(6):757-64

11 Harvey RG. A blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of borage seed oil and fish oil in the management of canine atopy, Vet Rec 1999,April 10 ;144 (15): 405-7.

12 Collier Pm, Ursell A, Zaremba K, Payne Cm, Staughton Rc, Sanders T. Effect of regular consumption of oily fish compared with white fish on chronic plaque psoriasis, Eur J Clin Nutr 1993 Apr;47(4):251-4.

13 Naldi L, Parazzini F, Peli L, Chatenoud L, Cainelli T. Dietary factors and the risk of psoriasis. Results of an Italian case-control study. Br J Dermatol 1996 Jan;134(1):101-6

14 Soyland E, Lea T, Sandstad B, Drevon A. Dietary supplementation with very long-chain n-3 fatty acids in man decreases expression of the interleukin-2 receptor (CD25) on mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes from patients with inflammatory skin diseases, Eur J Clin Invest 1994 Apr;24(4):236-42.

15 Corrocher R, Ferrari S, de Gironcoli M, Bassi A, Olivieri O, Guarini P, Stanzial A, Barba AL, Gregolini L. Effect of fish oil supplementation on erythrocyte lipid pattern, malondialdehyde production and glutathione-peroxidase activity in psoriasis. Clin Chim Acta 1989 Feb 15;179(2):121-31

16 Schena D, Chieregato GC, de Gironcoli M, Girelli D, Olivieri O, Stanzial AM, Corrocher R, Bassi A, Ferrari S, Perazzoli P, et al. Increased erythrocyte membrane arachidonate and platelet malondialdehyde (MDA) production in psoriasis: normalization after fish-oil. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1989;146:42-4

17 Kragballe K, Fogh K. A low-fat diet supplemented with dietary fish oil (Max-EPA) results in improvement of psoriasis and in formation of leukotriene B5. Acta Derm Venereol 1989;69(1):23-8

18 Grimminger F, Mayser P, Papavassilis C, Thomas M, Schlotzer E, Heuer KU, Fuhrer D, Hinsch KD, Walmrath D, Schill WB, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of n-3 fatty acid based lipid infusion in acute, extended guttate psoriasis. Rapid improvement of clinical manifestations and changes in neutrophil leukotriene profile. Clin Investig 1993 Aug;71(8):634-43

19. Mayser P, Mrowietz U, Arenberger P, Bartak P, Buchvald J, Christophers E, Jablonska S, Salmhofer W, Schill Wb, Kramer Hj, Schlotzer E, Mayer K, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Omega-3 fatty acid-based lipid infusion in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial, J Am Acad Dermatol 1998 Apr;38(4):539-47, Erratum in: J Am Acad Dermatol 1998 Sep;39(3):421

20 Bittiner SB, Tucker WF, Cartwright I, et al. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of fish oil in psoriasis. Lancet. 1988;1:378-380.

21 Oliwiecki S, Burton JL. Evening primose oil and marine oil in the traitment of psoriasis. Clin Exp dermato 1994 Mar ; 19(2) : 127-9.

22 Danno K, Sugie N. Combinaison therapy with low-dose etretinate and eicosapentaenoic acid for psoriasis vulgaris. J dermato 1998 Nov ; 25 (11) : 703-5.

23 Marsden JR. Effect of dietary fish oil on hyperlipidaemia due to isotretinoin and etretinate. Hum Toxicol 1987 May;6(3):219-22

24 Ashley JM, Lowe NJ, Borok ME, Alfin-Slater RB. Fish oil supplementation results in decreased hypertriglyceridemia in patients with psoriasis undergoing etretinate or acitretin therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988 Jul;19(1 Pt 1):76-82

25 Kokcam I, Naziroglu M. Antioxydants and lipid peroxydase status in the blood of patients with psoriasis. Clin Chim Acta 1999 Nov ; 289 (1-2) : 23-31.

26 Rollman O, Vahlquist A. Psoriasis and vitamin A. Plasma transport ans skin content of retinol, dehydroretinol and carotenoids in adult patients versus healty controls. Arch Dermatol Res. 1985;278(1):17-24

27 Conseil Supérieur d'Hygiène Publique de France. Les limites de sécurité dans les consommations alimentaires des vitamines et des minéraux. Éditions Lavoisier Tec&Doc ; 1996, 171.

28 Gieler U, Von Der Weth A, Heger M. Mahonia aquifolium - a new type of topical treatment for psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 1995;6:31-34.

29 Galle K, Müller-Jakic B, Proebstle A, et al. Analytical and pharmacological studies on Mahonia aquifolium. Phytomedicine. 1994;1:59-62.

30 Müller K, Ziereis K. The antipsoriatic Mahonia aquifolium and its active constituents; Pro and antioxidant properties and inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase. Planta Med. 1994;60:421-424.

31 Gieler U, Von Der Weth A, Heger M. Mahonia aquifolium - a new type of topical treatment for psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 1995;6:31-34.

32 Wiesenauer M, Lüdtke R. Mahonia aquifolium in patients with Psoriasis vulgaris - an intraindividual study. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:231-235.

33 Dreno B, Trossaert M, Boiteau HL, Litoux P. Zinc salts effects on granulocyte zinc concentration and chemotaxis in acne patients. Acta Derm Venereol 1992 Aug;72(4):250-2

34 Yamaoka J, Kume T, Akaike A, Miyachi Y. Suppressive effect of zinc ion on iNOS expression induced by interferon-gamma or tumor necrosis factor-alpha in murine keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci 2000 May;23(1):27-35

35 Verma KC, Saini AS, Dhamija SK. Oral zinc sulphate therapy in acne vulgaris: a double-blind trial. Acta Derm Venereol 1980;60(4):337-40

36 Dreno B, Amblard P, Agache P, Sirot S, Litoux P. Low doses of zinc gluconate for inflammatory acne. Acta Derm Venereol 1989;69(6):541-3

37 Meynadier J. Efficacy and safety study of two zinc gluconate regimens in the treatment of inflammatory acne. Eur J Dermatol 2000 Jun;10(4):269-73

38 Michaelsson G. Decreased concentration of selenium in whole blood and plasma in acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70(1):92

39 Michaelsson G, Edqvist LE. Erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase activity in acne vulgaris and the effect of selenium and vitamin E treatment. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70(1):92

40 Rosenberg EW, Kirk BS. Acne diet reconsidered, Arch Dermatol 1981; 117: 193-5

Order the nutrients mentioned in this article

Found naturally in the skin, this ingredient is used in the nutritional treatment of psoriasis

www.supersmart.com

Intensive rehydration for dry skin, as demonstrated in three clinical studies !

www.supersmart.com

Contains natural ingredients that have a positive effect on the mechanisms of skin ageing

www.supersmart.com

Ultimate marine collagen powder, in the form of hydrolysed peptides of type 1 collagen, a structural protein of the skin (powerful anti-wrinkle properties) and joints

www.supersmart.com

Healthy individuals now require a minimum dose of 1000 IU a day.

www.supersmart.com

Complete range of B vitamins directly usable by the body. New formulation with even greater bioavailability

www.supersmart.comFurther reading

10-08-2016

A true sign of the passing years, wrinkles are the inevitable consequence of ageing of the skin. Mrs Smith, a strong-minded woman in her fifties,...

Read more24-06-2019

Astaxanthin is a powerful natural antioxidant which continues to attract interest. Since the publication in November 2016 of our article entitled Astaxanthin - an exceptionally...

Read more04-03-2019

Essential for good health, vitamin D is primarily known for its vital role in mineralising the bones, joints and teeth. Its effects on the immune...

Read more© 1997-2025 Fondation pour le Libre Choix

All rights reserved

All rights reserved

Free

Thank you for visiting our site. Before you go

REGISTER WITHClub SuperSmart

And take advantage

of exclusive benefits:

of exclusive benefits:

- Free: our weekly science-based newsletter "Nutranews"

- Special offers for club members only